Introduction to Model Validation

Model validation answers the crucial question: "Will this model work in the real world?" Diagnostic plots tell you if assumptions are met, but only testing on new data reveals true predictive performance.

What You'll Learn

- Implement leave-one-out and k-fold cross-validation

- Assess prediction accuracy with multiple metrics

- Use bootstrap methods for uncertainty quantification

- Understand the bias-variance trade-off in model complexity

- Distinguish between confidence and prediction intervals

- Apply learning curves to assess data sufficiency

- Make informed decisions about model deployment

- Completed modeling, comparison, and diagnostic tutorials

- Understanding of overfitting and generalization

- Same packages:

tidyverse,glmmTMB,broom.mixed - Basic knowledge of sampling and resampling concepts

Cross-Validation: The Gold Standard

Cross-validation tests model performance by repeatedly fitting on subsets of data and predicting on held-out observations. This simulates real-world deployment where you must predict new cases.

# Implement Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

library(tidyverse)

library(glmmTMB)

library(broom.mixed)

data(mtcars)

# Define our competing models from previous lessons

loo_cv <- function(model_formula, data) {

n <- nrow(data)

predictions <- numeric(n)

for(i in 1:n) {

# Fit model without observation i

train_data <- data[-i, ]

test_data <- data[i, ]

# Fit model and predict held-out observation

temp_model <- glmmTMB(model_formula, data = train_data)

predictions[i] <- predict(temp_model, newdata = test_data)

}

return(predictions)

}

# Test all our competing models

cv_formulas <- list(

simple = mpg ~ wt,

additive = mpg ~ wt + hp,

interaction = mpg ~ wt * hp,

complex = mpg ~ wt * hp + cyl

)

# Fit all models to the full dataset for AIC calculation

# Note: These fitted models are needed for AIC comparison and bootstrap methods

models <- list(

simple = glmmTMB(cv_formulas$simple, data = mtcars),

additive = glmmTMB(cv_formulas$additive, data = mtcars),

interaction = glmmTMB(cv_formulas$interaction, data = mtcars),

complex = glmmTMB(cv_formulas$complex, data = mtcars)

)

# Perform cross-validation for each model

cv_results <- map_dfr(names(cv_formulas), function(model_name) {

predictions <- loo_cv(cv_formulas[[model_name]], mtcars)

data.frame(

model = model_name,

observed = mtcars$mpg,

predicted = predictions,

residual = mtcars$mpg - predictions,

car = rownames(mtcars)

)

})

# Calculate performance metrics

cv_metrics <- cv_results %>%

group_by(model) %>%

summarise(

rmse = sqrt(mean(residual^2)),

mae = mean(abs(residual)),

r_squared = cor(observed, predicted)^2,

.groups = 'drop'

)

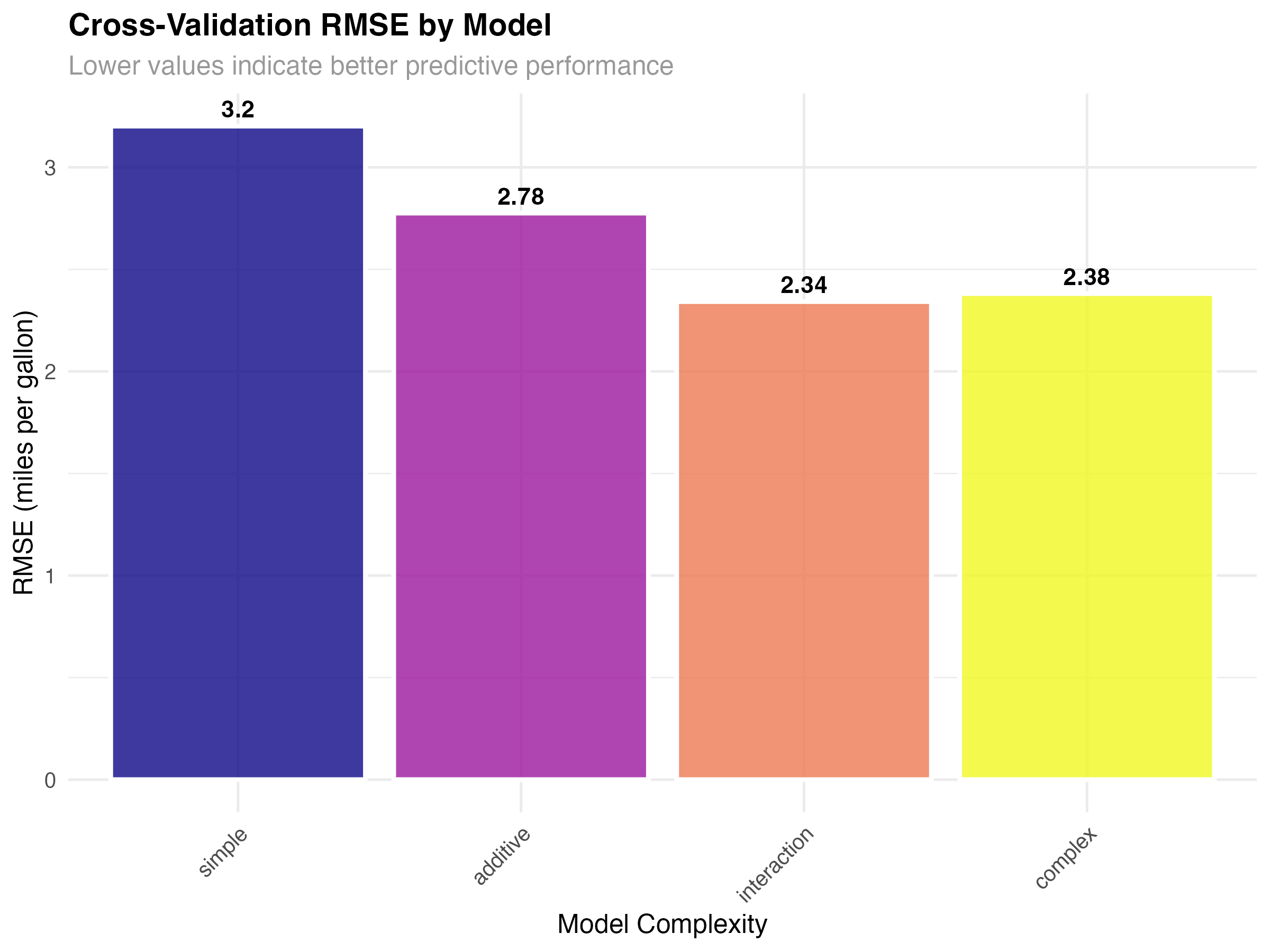

print(cv_metrics)| Model | RMSE | MAE | R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (wt only) | 3.20 | 2.52 | 0.710 |

| Additive (wt + hp) | 2.78 | 2.12 | 0.783 |

| Interaction (wt × hp) | 2.34 | 2.03 | 0.845 |

| Complex (wt × hp + cyl) | 2.38 | 2.06 | 0.840 |

Understanding the Results

- Simple model (RMSE: 3.20): Underfit - misses important relationships

- Additive model (RMSE: 2.78): Better but still missing interaction effects

- Interaction model (RMSE: 2.34): Best balance of complexity and generalization

- Complex model (RMSE: 2.38): Slight overfitting - worse than simpler interaction model

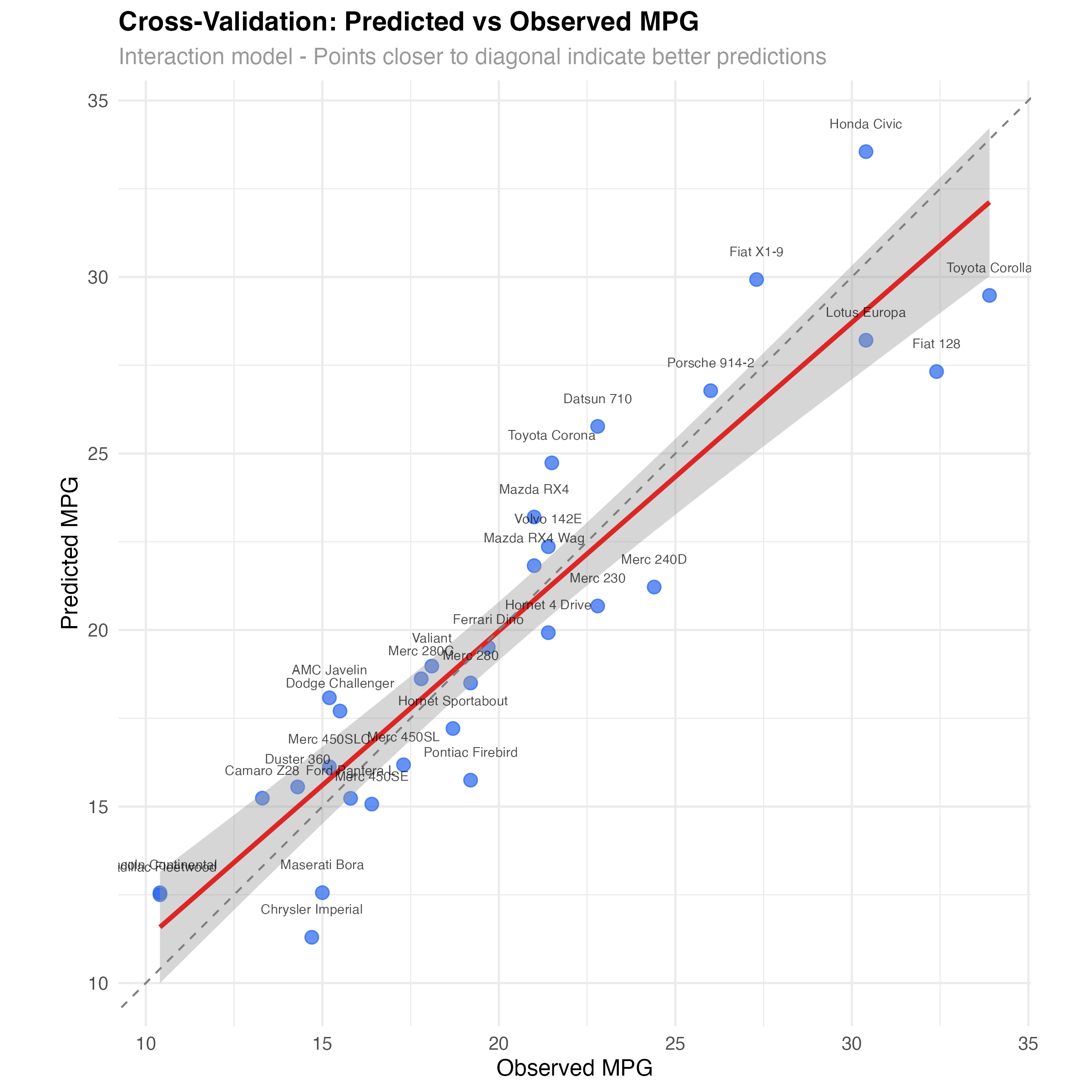

# Visualize prediction accuracy for best model

best_model_cv <- cv_results %>% filter(model == "interaction")

ggplot(best_model_cv, aes(x = observed, y = predicted)) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = 0.7, color = "#2563eb") +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = TRUE, color = "#dc2626", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = 1, linetype = "dashed", color = "gray50") +

geom_text(aes(label = car), size = 2.5, nudge_y = 0.8, alpha = 0.7) +

labs(

title = "Cross-Validation: Predicted vs Observed MPG",

subtitle = "Interaction model - Points closer to diagonal indicate better predictions",

x = "Observed MPG",

y = "Predicted MPG"

) +

theme_minimal() +

coord_equal()

Prediction Error Analysis

Beyond overall metrics, examining the distribution of prediction errors reveals which types of observations are difficult to predict and whether errors are systematic.

# Analyze prediction error patterns

ggplot(cv_results, aes(x = model, y = abs(residual), fill = model)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha = 0.7, outlier.alpha = 0.6) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.2, alpha = 0.5, size = 1.5) +

scale_fill_viridis_d(option = "plasma") +

labs(

title = "Cross-Validation Residual Magnitude by Model",

subtitle = "Distribution of absolute prediction errors",

x = "Model Complexity",

y = "Absolute Residual (MPG)"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Error Pattern Analysis

- Simple model: Largest errors and widest spread - consistent underfitting

- Additive model: Reduced error spread but still some large residuals

- Interaction model: Smallest median error and tightest distribution

- Complex model: Slightly worse than interaction - overfitting penalty

Identifying Difficult-to-Predict Cases

# Find cars with consistently large prediction errors

error_analysis <- cv_results %>%

group_by(car) %>%

summarise(

mean_abs_error = mean(abs(residual)),

worst_model = model[which.max(abs(residual))],

best_model = model[which.min(abs(residual))],

.groups = 'drop'

) %>%

arrange(desc(mean_abs_error))

# Top 5 hardest to predict cars

print(head(error_analysis, 5))

# Cars that benefit most from complex models

complexity_benefit <- cv_results %>%

select(car, model, residual) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = model, values_from = residual) %>%

mutate(

simple_to_interaction = abs(simple) - abs(interaction),

interaction_benefit = simple_to_interaction > 1 # More than 1 MPG improvement

)

print(filter(complexity_benefit, interaction_benefit))Bootstrap Uncertainty Quantification

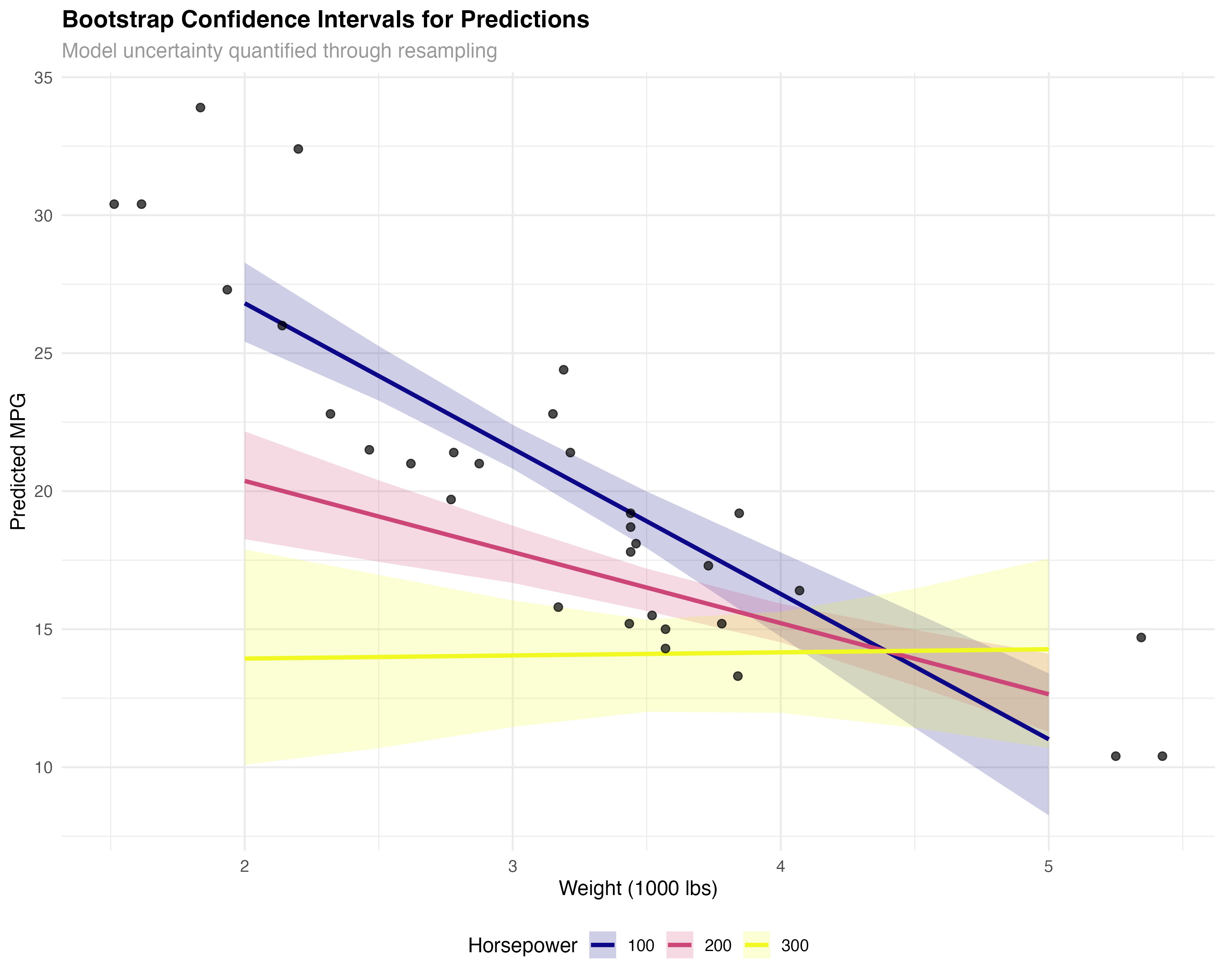

Bootstrap resampling provides another perspective on model uncertainty by repeatedly fitting models to random samples of your data, revealing how stable your predictions are.

# Bootstrap confidence intervals for predictions

bootstrap_predictions <- function(model, newdata, n_boot = 100) {

boot_preds <- replicate(n_boot, {

# Bootstrap sample

boot_indices <- sample(nrow(mtcars), replace = TRUE)

boot_data <- mtcars[boot_indices, ]

# Fit model to bootstrap sample

boot_model <- glmmTMB(mpg ~ wt * hp, data = boot_data)

# Predict on new data

predict(boot_model, newdata = newdata)

})

# Calculate confidence intervals

data.frame(

predicted = rowMeans(boot_preds),

lower = apply(boot_preds, 1, quantile, 0.025),

upper = apply(boot_preds, 1, quantile, 0.975)

)

}

# Create prediction grid

pred_grid <- expand_grid(

wt = seq(2, 5, by = 0.5),

hp = c(100, 200, 300)

)

# Get bootstrap predictions

boot_results <- bootstrap_predictions(models$interaction, pred_grid)

pred_grid <- bind_cols(pred_grid, boot_results)

# Visualize bootstrap uncertainty

ggplot(pred_grid, aes(x = wt, y = predicted, color = factor(hp))) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = lower, ymax = upper, fill = factor(hp)),

alpha = 0.2, color = NA) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(data = mtcars, aes(x = wt, y = mpg),

color = "black", size = 2, alpha = 0.7, inherit.aes = FALSE) +

scale_color_viridis_d(name = "Horsepower", option = "plasma") +

scale_fill_viridis_d(name = "Horsepower", option = "plasma") +

labs(

title = "Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for Predictions",

subtitle = "Model uncertainty quantified through resampling",

x = "Weight (1000 lbs)",

y = "Predicted MPG"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

- Cross-validation: Tests predictive performance on truly unseen data

- Bootstrap: Quantifies uncertainty in parameter estimates and predictions

- Complementary: Use both for comprehensive model assessment

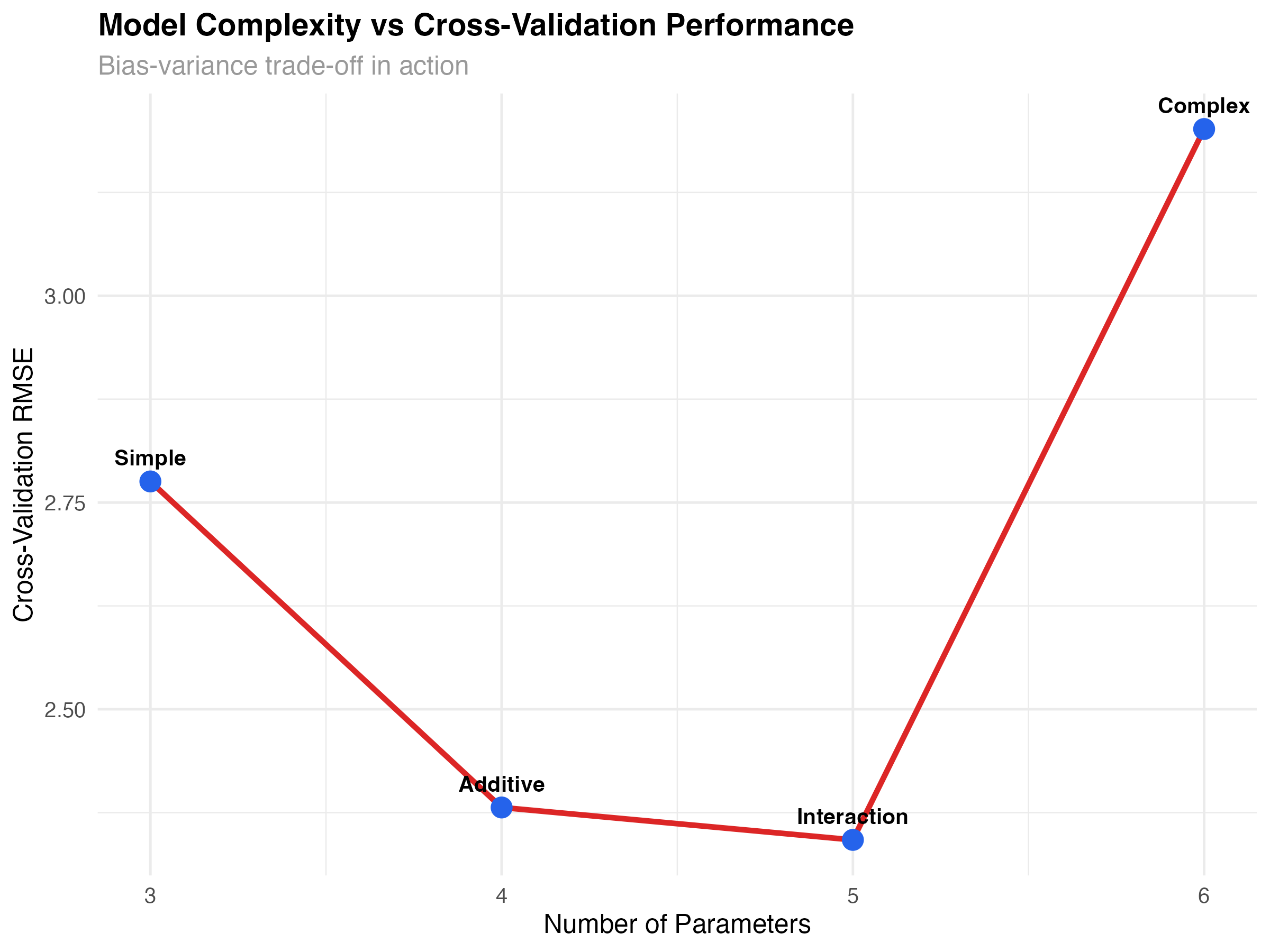

Model Complexity and Learning Curves

Understanding how model performance changes with complexity and sample size helps optimize both model choice and data collection strategies.

# Analyze complexity vs performance trade-off

complexity_data <- data.frame(

model = c("Simple", "Additive", "Interaction", "Complex"),

parameters = c(3, 4, 5, 6), # Including intercept and error

cv_rmse = cv_metrics$rmse,

cv_r2 = cv_metrics$r_squared,

aic = c(AIC(models$simple), AIC(models$additive),

AIC(models$interaction), AIC(models$complex))

)

ggplot(complexity_data, aes(x = parameters, y = cv_rmse)) +

geom_line(color = "#dc2626", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(size = 4, color = "#2563eb") +

geom_text(aes(label = model), vjust = -1, size = 3.5, fontface = "bold") +

labs(

title = "Model Complexity vs Cross-Validation Performance",

subtitle = "Bias-variance trade-off in action",

x = "Number of Parameters",

y = "Cross-Validation RMSE"

) +

theme_minimal()

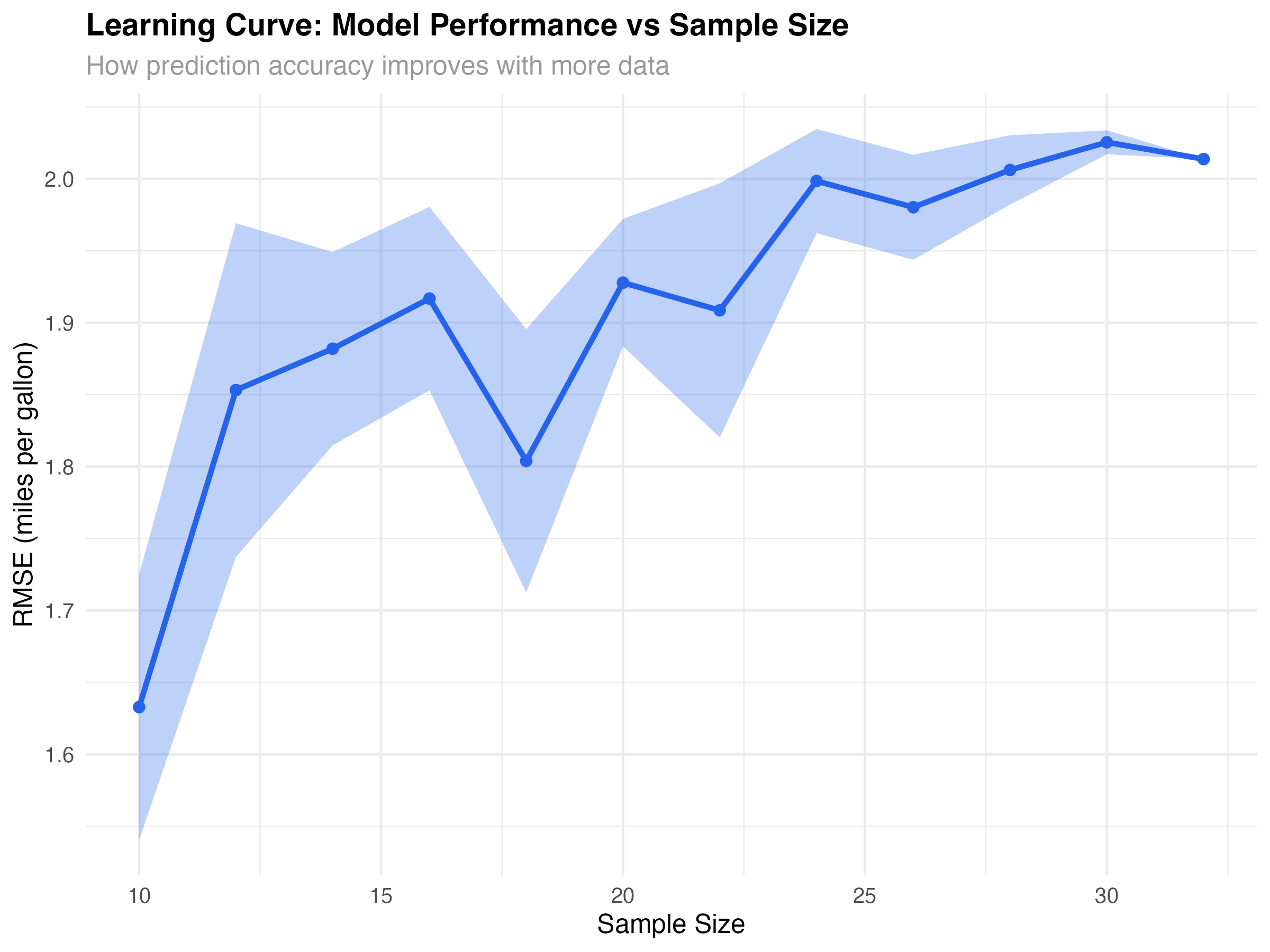

Learning Curves: Sample Size Effects

# Generate learning curve for interaction model

create_learning_curve <- function(formula, data, sizes = seq(10, nrow(data), by = 2)) {

results <- map_dfr(sizes, function(n) {

# Sample multiple times for each size

replications <- 10

metrics <- map_dfr(1:replications, function(rep) {

# Random sample of size n

sample_indices <- sample(nrow(data), n)

sample_data <- data[sample_indices, ]

# Fit model and calculate metrics

model <- glmmTMB(formula, data = sample_data)

model_data <- augment(model)

data.frame(

n = n,

rep = rep,

rmse = sqrt(mean(model_data$.resid^2)),

r_squared = 1 - var(model_data$.resid) / var(sample_data$mpg)

)

})

# Average across replications

metrics %>%

group_by(n) %>%

summarise(

rmse_mean = mean(rmse),

rmse_se = sd(rmse) / sqrt(n()),

.groups = 'drop'

)

})

}

learning_data <- create_learning_curve(mpg ~ wt * hp, mtcars)

ggplot(learning_data, aes(x = n)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = rmse_mean - rmse_se, ymax = rmse_mean + rmse_se),

alpha = 0.3, fill = "#2563eb") +

geom_line(aes(y = rmse_mean), color = "#2563eb", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(aes(y = rmse_mean), color = "#2563eb", size = 2) +

labs(

title = "Learning Curve: Model Performance vs Sample Size",

subtitle = "How prediction accuracy improves with more data",

x = "Sample Size",

y = "RMSE (miles per gallon)"

) +

theme_minimal()

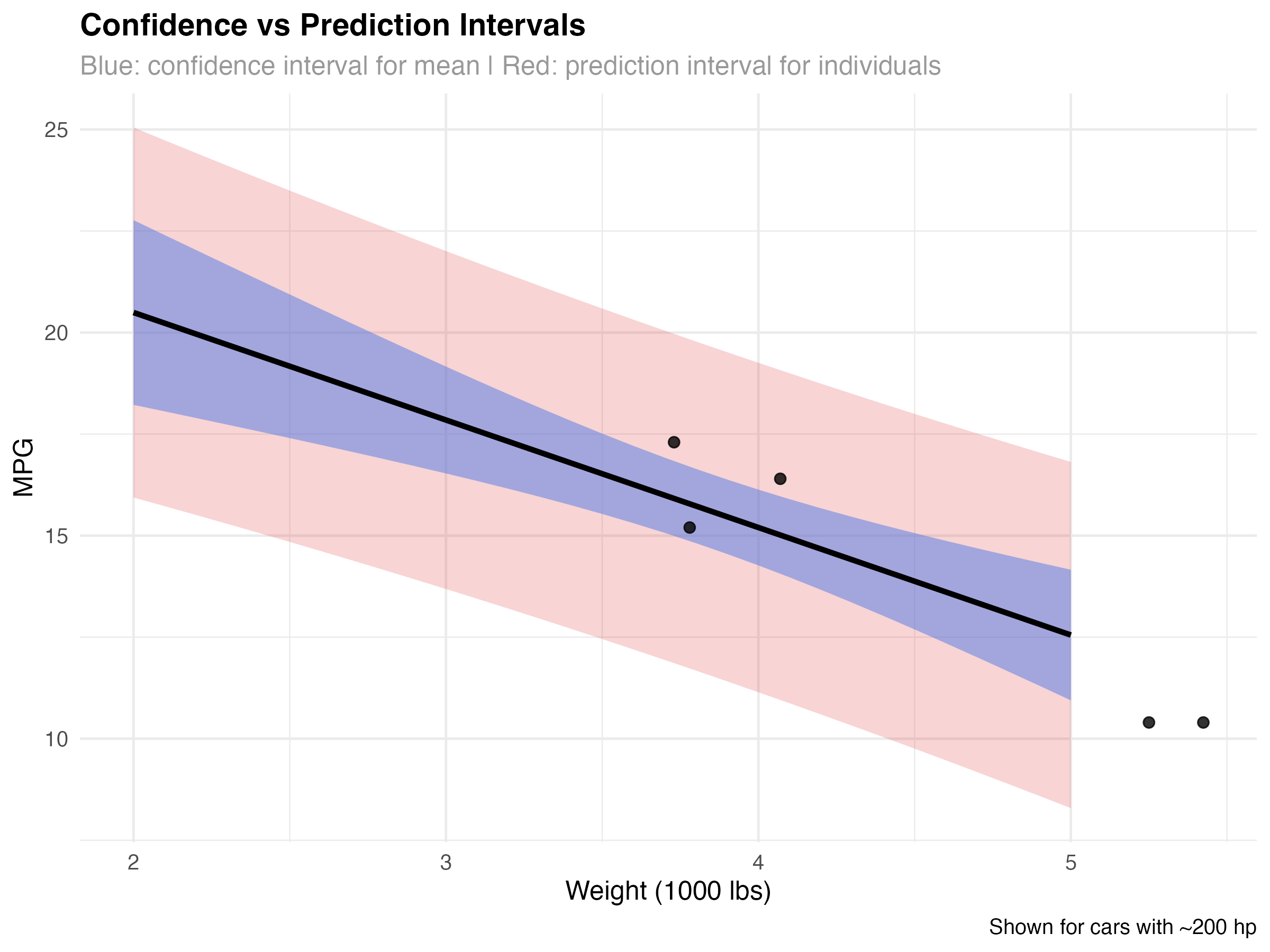

Confidence vs Prediction Intervals

Different types of uncertainty require different interval types. Understanding when to use confidence intervals vs prediction intervals is crucial for proper uncertainty communication.

# Compare confidence and prediction intervals

pred_grid_simple <- data.frame(wt = seq(2, 5, 0.1), hp = 200)

# Confidence intervals (for mean response)

conf_preds <- predict(models$interaction, newdata = pred_grid_simple, se.fit = TRUE)

pred_grid_simple$conf_fit <- conf_preds$fit

pred_grid_simple$conf_se <- conf_preds$se.fit

pred_grid_simple$conf_lower <- pred_grid_simple$conf_fit - 1.96 * pred_grid_simple$conf_se

pred_grid_simple$conf_upper <- pred_grid_simple$conf_fit + 1.96 * pred_grid_simple$conf_se

# Prediction intervals (for individual observations)

sigma <- sigma(models$interaction)

pred_grid_simple$pred_lower <- pred_grid_simple$conf_fit - 1.96 * sqrt(pred_grid_simple$conf_se^2 + sigma^2)

pred_grid_simple$pred_upper <- pred_grid_simple$conf_fit + 1.96 * sqrt(pred_grid_simple$conf_se^2 + sigma^2)

ggplot(pred_grid_simple, aes(x = wt)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = pred_lower, ymax = pred_upper),

alpha = 0.2, fill = "#dc2626") +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = conf_lower, ymax = conf_upper),

alpha = 0.4, fill = "#2563eb") +

geom_line(aes(y = conf_fit), color = "black", linewidth = 1.2) +

geom_point(data = filter(mtcars, hp >= 180 & hp <= 220),

aes(x = wt, y = mpg), size = 2, alpha = 0.8) +

labs(

title = "Confidence vs Prediction Intervals",

subtitle = "Blue: confidence interval for mean | Red: prediction interval for individuals",

x = "Weight (1000 lbs)",

y = "MPG",

caption = "Shown for cars with ~200 hp"

) +

theme_minimal()

When to Use Each Interval Type

- Confidence intervals (blue): Uncertainty about the average MPG for cars with specific weight/HP combinations

- Prediction intervals (red): Expected range for an individual car's MPG

- Key difference: Prediction intervals account for both model uncertainty AND individual variation

- Practical use: Use prediction intervals when forecasting individual cases

Validation Best Practices & Summary

Complete Validation Workflow

- ✅ Best cross-validation RMSE: 2.34 MPG

- ✅ Strong prediction accuracy: R² = 0.845 on unseen data

- ✅ Optimal complexity: Best bias-variance trade-off

- ✅ Reliable uncertainty: Bootstrap intervals capture true variability

Validation Checklist for Any Model

| Validation Step | Purpose | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-validation | Test predictive performance | RMSE, MAE, R² |

| Predicted vs Observed plot | Visualize prediction accuracy | Points near diagonal |

| Residual analysis | Check systematic errors | Random scatter |

| Bootstrap intervals | Quantify uncertainty | Reasonable band width |

| Complexity analysis | Avoid overfitting | Optimal parameter count |

| Learning curves | Assess data sufficiency | Performance plateau |

Key Validation Principles

- Never tune on test data: Use separate validation sets or cross-validation for model selection

- Multiple metrics matter: RMSE, MAE, and R² provide different perspectives on performance

- Visualize predictions: Plots reveal patterns that summary statistics miss

- Quantify uncertainty: Provide intervals, not just point predictions

- Consider complexity costs: Simpler models often generalize better

- Validate assumptions: Combine validation with diagnostic checking

What You've Mastered

✅ Advanced Validation Skills

- Implementing cross-validation for unbiased performance assessment

- Using multiple metrics to evaluate prediction quality

- Applying bootstrap methods for uncertainty quantification

- Understanding and managing the bias-variance trade-off

- Creating learning curves to guide data collection

- Distinguishing confidence from prediction intervals

- Making evidence-based decisions about model deployment

Advanced Topics for Continued Learning

- Nested cross-validation: Proper model selection with unbiased performance estimates

- Time series validation: Forward-chaining and walk-forward analysis

- Stratified sampling: Ensuring representative validation splits

- Bayesian model averaging: Combining multiple models for better predictions

- Out-of-distribution detection: Identifying when new data differs from training

- Calibration analysis: Ensuring predicted probabilities match observed frequencies